The Psychology Behind Pack Leadership: Does Cesar Millan’s Dominance Theory Still Hold Up?

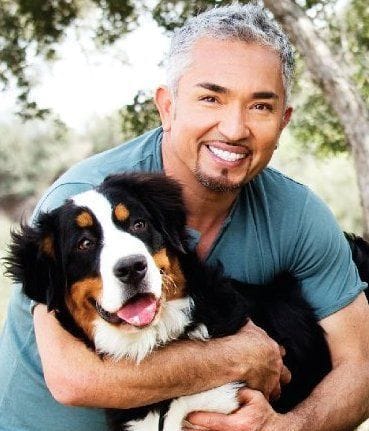

For millions of dog owners worldwide, Cesar Millan became synonymous with dog training. His television show “Dog Whisperer” introduced phrases like “calm-assertive energy” and “pack leader” into everyday vocabulary, promising to transform troubled dogs through dominance-based techniques. But as our understanding of canine behavior has evolved, so too has the debate surrounding his methods.

We dove deep into the research on wolf pack hierarchy, alpha theory, and what leading animal behaviorists NOW recommend for training your furry friend.

Today, we’re examining the scientific foundation behind pack leadership theory, exploring what modern research tells us about dog behavior, and investigating whether the dominance approach still holds water in the eyes of contemporary animal behaviorists.

The Origins of Alpha Theory

To understand Cesar Millan’s philosophy, we need to go back to where it all began: wolf studies from the 1940s. Researcher Rudolph Schenkel observed captive wolves at the Basel Zoo in Switzerland and documented what appeared to be a linear hierarchy with “alpha” wolves dominating subordinates through aggression and intimidation.

This research shaped decades of thinking about canine social structure. The logic seemed straightforward: dogs descended from wolves, wolves live in hierarchical packs with alpha leaders, therefore dogs must view their human families as packs requiring an alpha leader.

Cesar Millan built his training philosophy on this foundation, advocating that owners establish themselves as “pack leaders” through calm-assertive energy, physical corrections, and maintaining control over resources like food, space, and attention.

The Science That Changed Everything

Here’s where the story takes a crucial turn. In the 1990s and 2000s, wolf researcher L. David Mech, who had previously popularized the alpha concept, made a groundbreaking discovery while studying wolves in their natural habitat rather than in captivity.

What he found fundamentally challenged the alpha theory: wild wolf packs aren’t led by aggressive alphas fighting for dominance. Instead, they’re family units led by breeding pairs—essentially parents leading their offspring. The “dominance” behaviors observed in captive wolves were actually stress responses to unnatural living conditions with unrelated wolves forced together.

Mech himself has spent years trying to correct the misconception he helped create, stating that the alpha concept as applied to wild wolves is outdated and misleading. This raises an important question: if the foundation of pack leadership theory was based on misunderstood wolf behavior, how does that affect its application to domestic dogs?

What Modern Research Says About Dogs

Contemporary canine research has revealed that dogs and wolves, despite their genetic relationship, have significantly different social behaviors after thousands of years of domestication.

Studies published in journals like Applied Animal Behaviour Science have found that dogs don’t naturally form rigid hierarchical packs when left to their own devices. Instead, they form loose social groups with flexible relationships based on context, resources, and individual personalities.

Research from the University of Bristol and other institutions has shown that dogs primarily learn through association and consequence, not through perceiving humans as pack leaders requiring submission. Dogs respond to training because of conditioning, not because they’re trying to climb a social hierarchy.

Furthermore, studies examining stress hormones in dogs trained with different methods have revealed concerning findings about dominance-based techniques. Research published in the Journal of Veterinary Behavior found that dogs trained with aversive methods (including confrontational techniques like alpha rolls, scruff shakes, and forced submissions) showed higher levels of cortisol, indicating increased stress.

The Professional Consensus

Major veterinary and animal behavior organizations have issued position statements on training methods. The American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior (AVSAB) explicitly recommends against dominance-based training, stating that it can increase anxiety and aggression in dogs while being less effective than positive reinforcement methods.

The Association of Professional Dog Trainers and the International Association of Animal Behavior Consultants similarly advocate for science-based, positive reinforcement approaches. These organizations point to extensive research showing that reward-based training is not only more humane but also more effective for most behavioral issues.

Dr. Karen Overall, a veterinary behaviorist and researcher, has been particularly vocal about the problems with dominance theory, arguing that many behaviors interpreted as “dominance” are actually fear, anxiety, or simple learned responses to environmental cues.

Positive Reinforcement: The Alternative Approach

So what does modern science recommend instead? Positive reinforcement training focuses on rewarding desired behaviors rather than punishing unwanted ones. This approach is rooted in operant conditioning principles established by B.F. Skinner and refined through decades of behavioral research.

Key principles include marking and rewarding good behavior immediately, ignoring or redirecting unwanted behavior, and understanding that aggression and fear-based problems often require addressing the underlying emotional state rather than simply suppressing the behavior.

Studies comparing training methods have consistently shown that positive reinforcement produces dogs that are more confident, less stressed, and just as well-behaved as those trained with aversive methods—often more so. Research published in PLOS ONE found that dogs trained with reward-based methods showed better welfare outcomes and were less likely to display problematic behaviors.

Trainers using these methods focus on teaching dogs what TO do rather than punishing what NOT to do, creating clear communication without fear or intimidation.

Where Cesar Millan Gets It Right (And Wrong)

It’s worth acknowledging that not everything in Millan’s approach is problematic. His emphasis on exercise, mental stimulation, and owner confidence addresses real needs that many dogs have. A calm, confident handler is indeed more effective than an anxious, inconsistent one—though not for the reasons dominance theory suggests.

Millan’s success with many dogs likely comes from these elements rather than the dominance framework itself. When he insists on rules, boundaries, and consistency, these are training fundamentals that any behaviorist would support, even if the underlying theory differs.

However, specific techniques he’s demonstrated—including alpha rolls, helicopter leash corrections, and flooding (forcing fearful dogs to confront their fears)—are precisely the methods that research and professional organizations warn against. These techniques carry risks of increasing aggression, damaging the human-animal bond, and causing psychological harm.

Several of Millan’s television episodes have sparked controversy when dogs showed clear stress signals (whale eye, lip licking, freezing, cowering) that were interpreted as “submission” rather than fear or anxiety. This misreading of canine body language is one of the most significant concerns behaviorists have with his approach.

The Practical Implications for Dog Owners

So what should modern dog owners take away from this debate? Here are the key points based on current scientific understanding:

Your dog isn’t plotting to overthrow you as pack leader. Most behavioral problems stem from inadequate training, unclear communication, fear, anxiety, or unmet physical and mental needs—not from dominance struggles.

Relationship matters more than hierarchy. Building a positive relationship based on trust, clear communication, and mutual respect is more effective than establishing yourself as an alpha. Dogs are incredibly attuned to human behavior and learn best in environments where they feel safe.

Understanding motivation is crucial. Rather than assuming your dog “knows better” and is deliberately disobeying, consider what’s actually driving the behavior. Is your dog scared, excited, confused, or simply untrained? Addressing the root cause works better than punishing the symptom.

Body language tells the real story. Learning to read canine stress signals helps you understand when training methods are causing fear or anxiety, even if the dog appears “submissive.” Healthy training shouldn’t require making your dog afraid.

Finding Balance in the Debate

The controversy surrounding Cesar Millan’s methods reflects a broader shift in how we understand and interact with animals. As our scientific knowledge advances, approaches that once seemed reasonable are being questioned and refined.

This doesn’t mean everyone who has followed Millan’s advice has harmed their dogs, nor does it mean that all traditional training methods are inherently abusive. Context, degree, and individual animals matter tremendously.

What it does mean is that we now have better information and more effective alternatives. Just as medicine evolves beyond outdated practices as research advances, so too should our approach to animal behavior.

The Bottom Line

Current scientific consensus does not support the dominance-based pack leadership model that Cesar Millan’s philosophy relies upon. The research that originally established alpha theory in wolves has been debunked by its own author, and studies of domestic dogs show they don’t operate according to rigid hierarchies with humans.

Modern animal behavior science overwhelmingly supports positive reinforcement approaches as more effective, more humane, and better for the human-animal bond. Professional organizations representing veterinarians and certified animal behaviorists have issued clear statements recommending against dominance-based methods.

This doesn’t diminish the real help Millan has provided to struggling dog owners, nor does it mean every technique he uses is harmful. But it does mean that the theoretical foundation of his approach is scientifically outdated, and that dog owners now have access to better alternatives backed by decades of peer-reviewed research.

The question isn’t whether Cesar Millan’s dominance theory still holds up—the science says it doesn’t. The real question is whether dog owners are ready to embrace training methods that reflect our current understanding of canine psychology, even when it means letting go of appealing but outdated concepts like pack leadership.

Your dog doesn’t need an alpha. They need a patient teacher, a consistent guide, and a relationship built on trust rather than dominance. That’s not just more humane—according to the science, it’s also more effective.

Ready to explore positive reinforcement training for your dog? Consider consulting with a Certified Professional Dog Trainer (CPDT) or a veterinary behaviorist who uses science-based methods. Your dog—and your relationship with them—will thank you.